Mention a long-haired woman climbing out from your TV or a creepy little boy hiding under the table, and most people – horror fans or not – would shudder. These iconic characters (or ghosts) from Japanese horror (J-horror) films Ring and Ju-On have terrified audiences around the world and become part of popular culture.

J-horror is a sub-genre that rose to prominence in the 1990s and stood out for its unsettling atmospheres, suspenseful direction, dystopian visions and ghostly characters – a contrast to Hollywood’s bloody slasher flicks.

Taking a deep dive into the widesread influence of the J-horror movement are directors Jasper Sharp and Sarah Appleton with their documentary, The J-Horror Virus. The film features personal accounts from directors, writers and critics about the genesis, evolution and diffusion of these iconic films, why they were so successful and how they gave audiences sleepless nights.

This distinctive brand of made-in-Japan supernatural chillers seeped into the global consciousness at the turn of the millennium, with films featuring vengeful ghosts manifesting themselves through contemporary technology against a backdrop of urban alienation and social decay.

The J-Horror Virus charts its origins in Teruyoshi Ishii’s 1988 fake documentary Psychic Vision: Jaganrei (1988) and Norio Tsuruta’s seminal Scary True Stories (1991/92) straight-to-video series, through key titles as Hideo Nakata’s Ring (1998), Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (2001) and Takashi Shimizu’s Ju-On: The Grudge (2002).

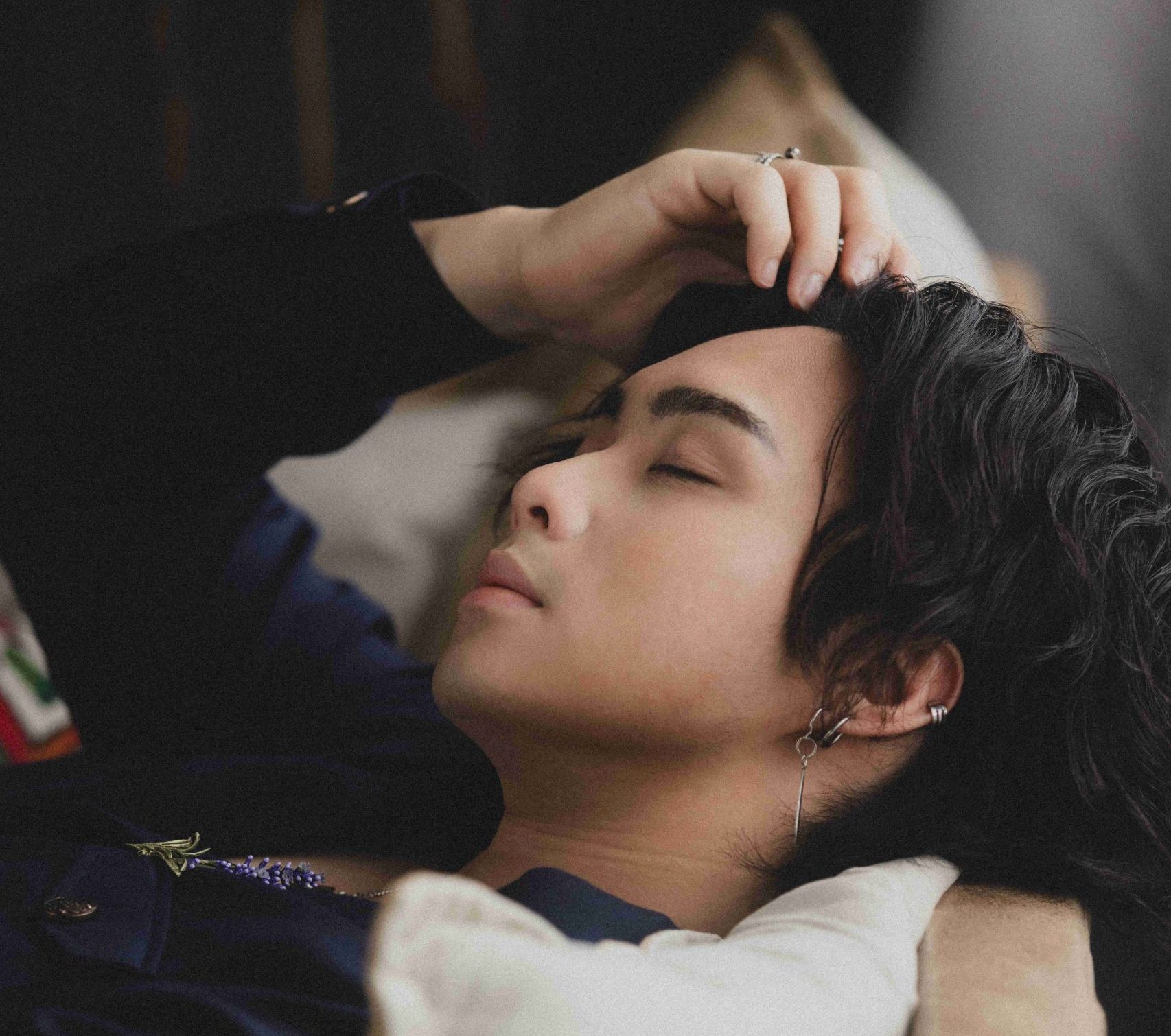

SG Magazine caught up with Sharp, who is also an author specialising in Japanese cinema, when he was in Singapore during the Japanese Film Festival 2023. Here, he shares about the inspiration behind the documentary, and his thoughts on the J-horror phenomenon.

What inspired you to make The J-Horror Virus, a documentary about Japanese horror movies from the 1990s?

I’ve been writing about Japanese films for 25 years now, and I’m interested in all aspects of Japanese films. In the West, everyone is aware of Japanese horror movies. I think they’re the biggest cultural impact on Japanese cinema for a long time.

But my partner [and co-director] Sarah, she’s the big horror fan, although she doesn’t know much about Japanese films. She just made a documentary about footage horror, or found footage phenomenon, like The Blair Witch Project. She really wanted to do a follow-up, and she knew that I knew about cinema. So she was like, we’ve got to do a J-horror documentary! She was definitely pushing for it.

When did your fascination with Japanese movies begin?

We had a legendary cinema in London called the Scala. It’s gone now. They would play like triple double and triple bills, where you pay like four pounds to sit there all night. Where I grew up in the real countryside in Devon, we didn’t really have any cinemas so I had been reading a lot about films that I couldn’t see.

When I moved to London, I used to go to the Scala every night after work and sit by myself watching all these films I’d never heard of. One night it was a Japanese screening of Kōji Wakamatsu’s Violated Angels, and The Ballad of Narayama. I think I’d read about the Wakamatsu film, which was why I thought, well, I have to go and see this. I didn’t understand it, and I didn’t really like it. But The Ballad of Narayama, I had never seen anything like it because it was made almost like a nature documentary; it just looked beautiful.

In the making of the documentary, you interviewed a number of renowned directors and writers, like Kiyoshi Kurosawa (writer/director of Cure and Pulse) and Takashi Shimizu (creator of the Ju-On series). Were there any surprising things they revealed that you didn’t know about previously?

I always thought J-horror began with Norio Tsuruta’s straight-to-video series called Scary True Stories. And so I contacted Tsuruta, and he said, I’d be honoured but one of my influences was the film Psychic Vision: Jaganrei by Teruyoshi Ishii. This was a straight-to-video fake documentary about a pop singer where they had ghost recordings of her on the audio tapes. When they looked at photos of her, there was always a ghost in the background.

So this, he said, was the very first J-horror movie, and I have to interview Ishii. I’d never heard of Psychic Vision before! So that was the big discovery, finding the very first J-horror movie.

Besides the fact that the films were well-written and well-made, do you think that the situation at the time, like the flagging economy, contributed to the sense of alienation and created a demand for such films?

Yeah, I think there’s definitely the economic situation [that contributed to it]. You could feel it in a lot of the J-horror films. That sort of feeling of despair. But that wouldn’t explain why it was a global hit, though, I think that maybe it was just in the right place at the right time. Because the American horror [at that time] was just Friday The 13th or Scream or something, it was just nothing to be treated seriously.

I put Ring at the very beginning of the historical narrative which has that very unsettling atmosphere, even though it doesn’t really have any violence. So I think it reminded us what horror could be globally; it should be about scaring people, not shocking them.

Then again, it came out the same time as The Blair Witch Project. They had a similar vibe and did something very different from what you would have expected. They caught our imagination in a similar way.

How would you define fear in the context of Japanese society?

I think it’s all about social alienation. You could be in the middle of Tokyo, Shinjuku or Shibuya, in very crowded areas where no one really knows each other. Maybe there’s a feeling that there’s no sense of community, that people are estranged from their environment.

The fear is that you have this feeling of group solidarity that’s an illusion, and suddenly someone will turn out to be a serial killer or murder or ghost. And you didn’t know.

Do you think that Hollywood versions of the films have done us justice to the original?

In America, they always see the monster or ghost as something to fight against, like an enemy. It’s always something outside of yourself. In Japan, it’s very much about the ghosts or scary things that come from within you, that it’s your perception. And there’s the moral ambiguity about things.

I don’t know how much Hollywood or Western horror has changed its philosophy because of that. I think there are films to deal with that kind of feeling, that the evil might be within you or society, not threats from the outside. Films like Smile and It Follows have taken that approach.

What is your favorite J-horror film?

Cure. Well, it’s not truly J-horror, but you know, Kiyoshi Kurosawa said it was made at the same time as Ring and he was then exploring his own filmmaking ideas. My other favourites are Pulse and Uzumaki. Uzumaki is about a town that is invaded by spirals; it’s very surreal.

What would you recommend to a new generation who want to explore the J-horror genre?

You could watch Pulse now, because this was made in the very early days of the Internet.

It’s all about social alienation, and how the internet would lead to this sort of draining of your soul and this lack of community. And this was made in 2000. I think it was just too ahead of its time, so it wasn’t successful then. If you watch it now, it has definitely touched on something.

You know, there’s scenes where people don’t die by death; they just fade away into this dark shadow on a wall and there you are, like a stain on the wall. It reminded me of the time during Covid where I had some friends who died. You would just see this email report, you know, on Facebook, about so and so who died recently. And everyone would post their comments. You couldn’t go to the funeral because we all sat at home in the lockdown. It was almost like there was nothing to mark their existence anymore. Just this sort of digital trace on Facebook.

So I think that’s what’s happening to society in general now. We don’t deal with people as people anymore. The way we communicate with people on social media is not the same as face to face. I guess that’s something the younger generation could potentially relate to.

The J-Horror Virus is still making its way round the festival circuit. Catch more Japanese films at the Japanese Film Festival happening from now till Dec 20. Visit jff.sg for more information.