Singapore has a way of really milking a milestone. It seems like just yesterday that corporations, small brands, even hawkers, were jumping on the bandwagon to partake in the giant publicity stunt that was SG50. The nation as a whole has barely recovered from it, and 2019 is quickly shaping up to be no different. With every single event, launch and product imaginable themed after the Singapore Bicentennial, it’s going to take a Birdbox-scaled feat to get through the rest of the year without hearing about our 200th anniversary. And we’re already off to a bad start.

Soon after announcing plans for the Bicentennial, the Singapore Bicentennial Office (SBO) received accusations that it was condoning and even celebrating colonialism. They’ve since backpedaled in rather embarrassing ways, including reframing the programming as a “commemoration” rather than a celebration, and going so far as to extend the timeline of retrospective history an additional 500 years before 1819—effectively defeating the purpose of a Bicentennial anniversary. Although admittedly “Singapore Septcentennial” doesn’t have as nice a ring to it.

Then there was the gimmick of making Raffles disappear quite literally from the land—only to restore him to his former glory within a day. In a follow-up move that stank of insincerity, SBO introduced four additional statues of lesser-known historical personalities to stand alongside Raffles, to explicitly convey that Singapore’s progress was not the Englishman’s doing alone.

Photo credit: Singapore Bicentennial Office

All this, in an effort to play down the textbook-endorsed narrative of the British lifting our poor fishing village out of squalor.

To that end, numerous representatives from the SBO have taken pains to clarify that “it’s not about celebrating colonialism”. “It’s about looking at every aspect in the entire journey, and all the different characters that joined us at different times,” said Minister Josephine Teo, Co-Chair of the Ministerial Steering Committee for the SBO, at a press briefing ahead of the Bicentennial’s official launch.

As such, a full year of events and festivals await. In March, the Singapore Heritage Festival will return with events themed to the Bicentennial; later in the month, a new festival called Find Your Place in History will bring visitors around projection installations to learn more about less prominent points in our history, in what an SBO representative called the “darker sister to i Light”. June holds immersive experiences in Fort Canning detailing our 700-year history, while new exhibitions in August will look at nation-building in the “early days” (that’s the aforementioned 500 years before 1819).

Sails Aloft at i Light Singapore 2019. Photo courtesy of Urban Redevelopment Authority

But programming has been lacklustre thus far. Key events in the arts calendar such as i Light Singapore and the newer Light to Night Festival, formerly vibrant and well-attended among the public, suffered in terms of creative output in an effort to bend to the theme.

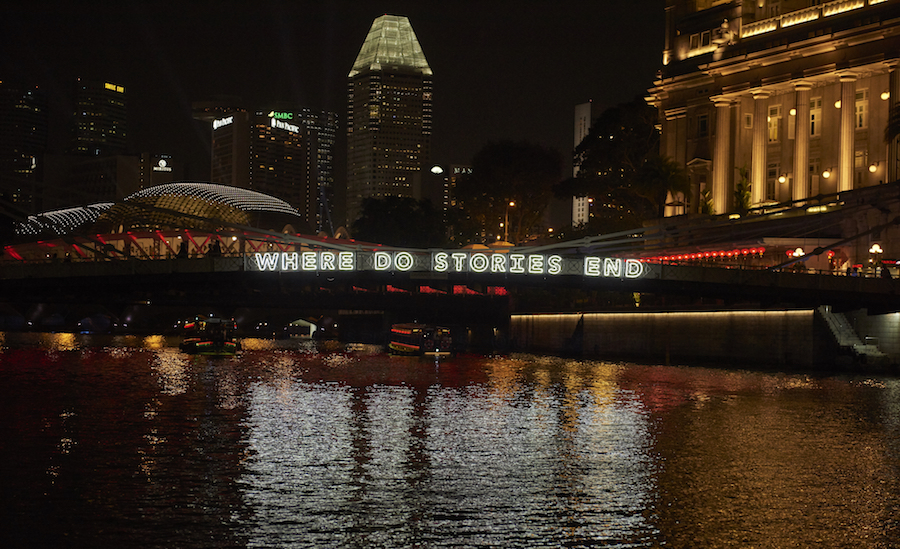

A reduced preparation time could have contributed to that. Typically held in March along the Marina Bay promenade, this year’s edition of i Light was moved forward to late January to coincide with the Bicentennial launch. Gone were the expansive, visually dazzling works that championed sustainability; in their place were uninspired, stilted pieces that spoke to specific moments in Singapore’s 700-year history, but left you walking away indifferent. Specifically curating works to the theme ‘Bridges of Time’ limited many of the installations to the various bridges along the Singapore River—which not only alienated visitors on foot, but also took away from the fun of getting up close and personal with an artwork.

Within the same month, this year’s Light to Night Festival saw more misses than hits. The festival’s projection mapping series on the facades of Civic District institutions returned, bearing good intentions but forgettable illustrations. Multimedia tributes paid to William Farquhar and composer Zubir Said felt more cursory than sincere. And a site-inspired interactive theatre piece titled Shadows in the Walls, touted as a highlight of the festival, took visitors through the National Gallery Singapore where roving actors put on cringe-worthy performances honouring lesser-known pioneers in Singapore’s history.

Sayang di Sayang, a tribute to Zubir Said

But boring art is not the Bicentennial’s biggest fault. Perhaps most troubling in all of this is how the underlying portrayal of Raffles remains unchanged. Singapore’s pre-1819 founders may be receiving more attention, but the pandering programming still conveniently ignores the British’s offenses as colonisers.

Commissioned programmes like the new augmented reality trail BALIKSG paints Raffles as a friend, allowing you to converse with him about signing the 1819 treaty—a bizarre thing to highlight, given that the treaty gave the British East India Company the right to set up a trading port on the island, marking Singapore as a British settlement henceforth.

While there have been some exhibitions that have dared to take a different stand, just as many skeptics have questioned their genuineness. An ongoing exhibition at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Raffles in Southeast Asia: Revisiting the Scholar and Statesman, paints the coloniser in a less than flattering light, pointing out his errors and outdated prejudices in curating culture during his time in Southeast Asia.

In a viral Facebook post shared on Feb 12, local author Alfian Sa’at pointed out the hypocrisy in presenting a show meant to undermine Raffles that still placed him at the centre. Sharing his frustrations after leaving a Q&A with the curator of the show, the vocal personality called out the curators for defending Raffles’ actions as being symptomatic of his time.

“I found this deeply troubling, because it smacked of wrapping Raffles up in a bubble wrap of immunity, as if he was simply acting out a historically predetermined role and that any attempt to critique him would be accused of as presentism,” Sa’at wrote.

Fellow writer and attendee of the talk Ng Yi-Sheng echoed these grievances in a post of his own. He criticised the exhibition for downplaying the significance of Raffles’ crimes, playfully mocking the colonial oppressor’s omission of key aspects of culture when it itself “erased the bloodshed of colonial violence”.

Indeed, it becomes problematic when even the government’s attempt to critically reevaluate a time-worn narrative presents the only faults committed by Raffles as mere human errors. If Singapore is sincere about wanting to present a fair picture of the country’s long, multi-layered history, we cannot simply brush aside Raffles as being a stupid white man “for his time”; nor colonialism as an unfortunate by-product of his misjudgement.

Photo credit: Vincent Ng

Logistically, it is not feasible to scrap many of the events to come—besides, some definitely do look promising. Two programmes happening in October will shine a light on Malay communities and non-European perspectives from the 16th to 19th centuries. But there needs to be a more concerted effort to objectively present history—even if it means confronting the uncomfortable reality that the founder of modern Singapore was an intrinsically bad man.

We’re not here to start a debate on Raffles’ contributions; there is a time and place for that. But subverting the narrative to bring home an unconcerted point and in the process reinforce existing messages is pointless to a disengaged audience. This country’s citizens are not dense; we’ll know to stop attending arts events when they all start sounding the same. Here’s hoping it at least got people thinking of the Singapore to come in the next 200 years.