Last weekend, we were blown away by the second instalment of Human Library Singapore. The mobile human-loaning library provided a space for people from very different walks of life to share their personal experiences with the participants, and answer any questions they may have candidly. If you weren’t at any of the 1,500 reading slots last Sunday (Mar 5), fret not—we took the liberty to speak to four of the 47 human books to share their stories: an ex-offender, a HIV patient, a Vietnamese refugee and a transgender woman.

Rather than using labels to describe them, there’s a lot more Singapore can do to support and understand these marginalized people. We could perhaps “exercise more empathy” as ex-offender Stanley suggested, or “volunteer in organizations” to understand Vietnamese refugees like Yen Siow. Or maybe the “acceptance should come from the people on top (government) and the rest will follow suit”. Here, we uncover their stories.

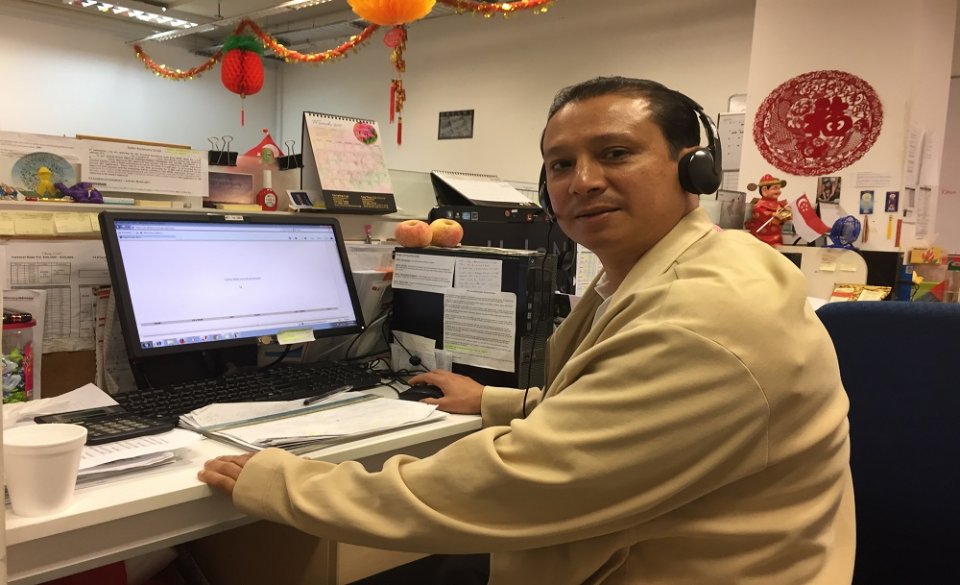

Stanley Ter, ex-offender and telemarketer, 48

What’s it like being an ex-offender in Singapore?

Of course there is some kind of distrust between the public and us in the beginning. But trust will be regained along the way. I think with Yellow Ribbon Project, the public learns more about ex-offenders now. And for the ex-offenders, sometimes without relatives or friends, learn how to interact with people. People sometimes have a different idea of your criminal offence, for example, drug trafficking used to mean you sell drugs to people. But now, if you share with someone to buy the drugs, it’s also categorized under that offence. People also tend to think offences like theft and drunk driving is more acceptable than serious crimes like rape and murder.

What’s it like being in jail in Singapore?

Nowadays, living conditions inside prison have improved greatly compared to the ’80s and 90s. We used to sleep on straw mats against uneven floors, and when it gets stuffy in the room, we make our own fans by using rice to stick the ends of a paper together. But it wasn’t allowed, so the officers do spot checks on us. Now, the floors are well-cemented; the toilets are cleaner; the rooms are more spacious and there’s even a “blower” in the rooms for better ventilation.

Were there extra challenges when you were looking for a job?

Thankfully, my company supports Yellow Ribbon Project and knows my past, so my situation is favorable. But unfortunately, some companies tend to be exploitive because they know a lot of people are waiting to get the job. Sometimes, we get treated like foreign workers. But in the late ’90s, I went for an interview and indicated on an application that I have criminal record. So the person called back and asked me what offence it was specifically, so I told them. But the company never got back.

HIV patient, 21

What’s it like being a HIV patient in Singapore?

It is a “don’t ask, don’t tell” situation—people don’t ask because HIV and AIDS has been associated with the LGBT community for a very long time. My community has rarely been in the spotlight because of this. The disease itself is less harmful to the body than other major immunodeficiency viruses (and) yet it has never been publicly known to the public. As a result, many people whom are not educated about it avoid the topic altogether. Many of us rarely disclose our status, even to our close friends, also because we got it from sex, which is mostly a taboo topic in Asian culture. The fact that we got it from sex automatically labels us as “dirty” people.

What was your initial reaction to your diagnosis and how did you overcome it?

It was one of the regular HIV testing schemes I signed up for where my test results will be used for research. When my test results were out, I was brought into a room with one of the counselors. He told me, “I’m sorry, you are HIV positive”. I remember losing focus as I stared at the diagnosis paper. I thought I came to terms with it and acted cool like, “Oh okay, I have it now. What’s next? Where should I get treatment?” I felt as if I did not deserve the pity or help, because I asked for it. I wanted sex and I cared less about the aftermath. At one point, I thought of attempting suicide to end it all. But I told myself that HIV is just an obstacle.

How did people react when you first told them about your illness?

At first, I hid the fact that I might be HIV positive. I was worried about what they would say when they found out the truth. I did eventually tell a few friends about my illness, those that I felt comfortable with. They all reacted in shock, and asked generic questions like how much medication I have to take and how much it costs. After that they did not seem to mind that I live with the virus and continued on as if we never did talk about it at all. But honestly that’s the best anyone in my community can hope for when we disclose our status. The virus is not lethal to anyone outside of our bodies as long as we adhere to medication, so we are not walking time bombs. We like to be treated for not what we have but what we can be in our own lives.

Yen Siow, Vietnamese refugee and founder of Discovering without Borders, 40

What’s it like being a Vietnamese refugee in Singapore?

Being a former refugee feels strange to say the least. My “happiest” memory was when I was given a can of Fanta for the first time and I really enjoyed the refreshing cold sweet drink. I am grateful for the help that Singapore gave to refugees, despite having limited resources.

What are you currently work as?

I started my own social enterprise Discovering without Borders, where we conduct STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) educational workshop for children of all abilities after realizing some children are falling behind on their studies because they couldn’t cope with the rising cost of tuition and enrichment classes.

Why did you have to leave your country?

My family escaped Vietnam because we faced severe persecution from the new government. It was a difficult decision for any person to leave their country, but I understand that my parents chose to risk everything to pursue freedom and a better life for their children.

Tell us about your journey from Vietnam to Singapore.

In October 1980, 13 of us boarded a small fishing boat intended for 10 people with 69 other refuges. The flimsy boat’s engine even died a few times, and other passing ships refused to help. But, on the morning of the fifth day, we were spotted by a Norwegian oil tanker Berge Tasta that finally rescued us after sailing away at first. The Norwegian crew treated us with warm hospitality even though we were different. My father told me that one of our first meals on the ship was a delicious array of 300 boiled eggs.

The Singapore government had a strong policy that refugees would only be accepted to the UNHCR refugee site if the country that rescued the boat people will be financially responsible for each refugee. The Norwegian government made a deal with the Singapore government that they would sponsor my family $3 per person per day and that within four months, they would re-locate us all to Norway so that we would become Norwegian citizens.

At the UNHCR refugee camp, some families lived in proper shelters while others slept in tents. The camp also received donations of second hand items from local churches and the community at large. The refugee camp was mainly a transit point for families during the resettlement process.

Sandhiya Thomas, transgender woman and research facilitator at NUS’ CARE, 39

What’s it like being a transgender woman in Singapore?

Being a transgender in Singapore is really not easy. I need to work extra harder so that I can be visible. We face discrimination when applying for a job, like my IC says I’m female, but people question why your voice is different. And they assume their customers or clients are uncomfortable with us. You also can’t apply for rental housing because in order to obtain a house, you need to share with someone else and be above 35 years old. On top of that, we can’t buy insurance because we are considered as the high risk group, after knowing the hormone pills we are taking.

How did your family and friends react around you when you made the transition?

Things were not easy at home, and of course in the beginning, my family were angry and disappointed. It took me 15 years to make them understand why I made the transition.

So, they assume you get into sex work once you are a transgender; I have to prove that assumption is wrong. I have to take every opportunity that comes my way; even it means to work as a toilet cleaner to prove that I can work too.

If you’re excited for the next edition of Human Library, it’ll happen some time in mid-2017 at Taman Jurong CC. The line-up however will only be confirmed after a tedious process of curation. For more updates, go to their Facebook page.