It’s not very often that Singapore becomes a place to shoot films in these days, but when they do, we can’t help but feel extra excited. Now, there’s going to be an entire series dedicated to the screening of these foreign, yet local films. State of Motion, a visual arts series organized by Asian Film Archive, is part of the organization’s efforts to preserve the rich film heritage of Singapore and Asia and to cultivate an appreciation of this art form. Themed “Through Stranger Eyes”, the five films, all made by foreign filmmakers and many of which were previously banned, will delve into the history of Singapore cinema by exploring the actual locations of these films in Singapore and the nation’s mutability as an actor. We were incredibly curious as to why the series began and well, how the previously banned films get screening permits again (considering our love for censorship). Here, we speak to the producer of State of Motion, Thong Kay Wee and curator of the series, Kent Chan.

How did you go about selecting these films?

They present a post-independent Singapore that is recognizable but unfamiliar, capturing intriguing scenes of a transforming post-independent Singapore. The concept for the 2017 edition came about as we considered how Singapore was a destination for foreign filmmakers in the 1960s-80s. Cinema beyond its artistic and entertainment value, is a document of time. The films, as the theme of ‘Through Stranger Eyes’ suggests, are based on different perspectives from around the world and were chosen not just because of their images of Singapore, but also because it shows how our nation state was perceived socially and politically by foreign and local filmmakers. The film locations were selected based on their presence in the films. This tedious and meticulous process of selection, research and consolidation, curated by Kent Chan and supported by our film researcher Toh Hun Ping, eventually influenced the scope and directions that the exhibition would take. In today’s fast-paced life, spaces and history are often only considered through one’s own eyes.

We know the most of the films featured were previously censored or banned. How were you able to screen them this time?

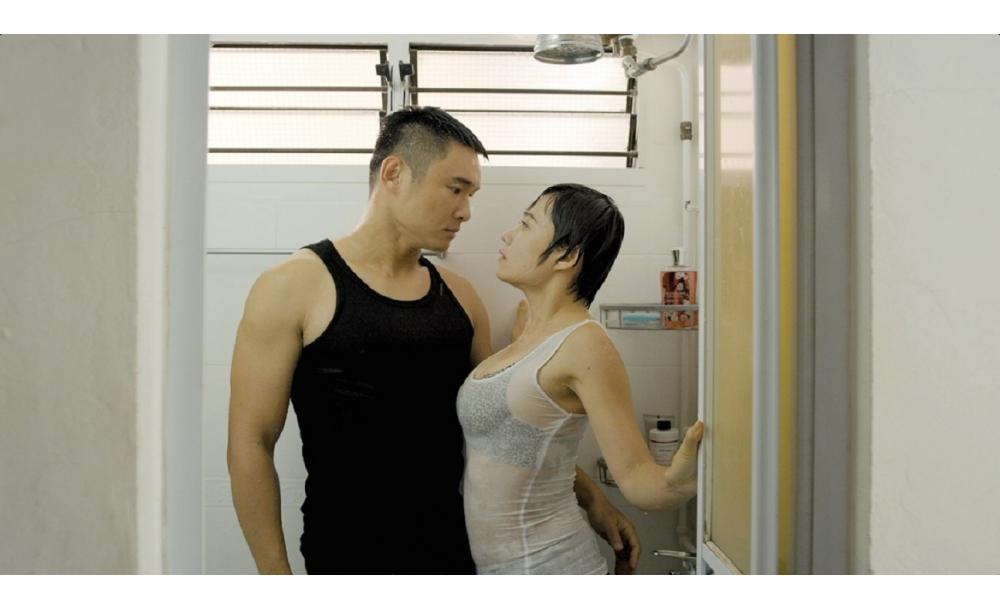

Only two of the five films showcased were banned previously—Ring of Fury (1973) and Saint Jack (1979). The ban on Ring of Fury was lifted in the 1990s, and the ban for Saint Jack lifted in 2006. The former is Singapore’s first and only martial arts action film of a humble noodle-seller turned pugilist battling against gangsters led by a man in an iron mask. It was banned for its portrayal of gangsterism at a time when Singapore was aggressively “cleaning up”. It was also shown during Screen Singapore: A Festival of Singapore Films in 2005. Saint Jack depicts an American pimp named Jack Flowers, who tries to make his fortune in Singapore. Adapted from a 1973 novel by Paul Theroux, the film essentially depicts a man’s desire to forge a reasonably honorable life in a dishonorable profession. As the first Hollywood movie to be filmed entirely on location in Singapore, it was also banned for decades because of its unsavoury portrayal of the nation-state in the 1970s. The ban was lifted in 2006 and the film had its first official public screening in Singapore in the same year. The films depict a Singapore that is not recognizable today.

Why is this series important?

State of Motion highlights not just interesting films that feature different historic representations of Singapore, but also the work of artists that have been inspired by film and history. Though most people would be familiar with the locations, such as Far East Plaza and Golden Mile Food Centre, we hope that through the films and artworks exhibited at each locale, visitors discover the rich film history at these sites and see these places through stranger eyes, to uncover the many different imaginations of Singapore.

What sort of research went into putting together the series?

Basically, we’ve tapped into artist, filmmaker and researcher, Toh Hun Ping’s extensive research on film locations from films shot in Singapore in the 20th century. That was the starting point that allowed us to decide upon the film and locations to venture into. There’s also research consisting of news reports and other writings regarding the films and the stories behind them that shapes a narrative around Singapore’s relationship with film and culture in the post-independence decades. Finally, there’s research on an individual level by each of the artist as they look sought the context in which to situate their work in.

What were some of the most interesting discoveries you made that will surprise the average Singaporean?

My pick would have to be Saint Jack. Just the fact that it featured so much of the former Bugis Street and its former dwellers that it comes as a shock how much we’ve changed. I mean, it’s Singapore and we are all about the point whereby we are numb to changes, but this one still packs a punch. Maybe because Bugis lies within the designated Arts and Heritage District that it’s ironic to see how organic the original Bugis Street would have fit into the category of “heritage”, but yet no longer exist.

Most recently, Rajagopal’s A Yellow Bird showed Singaporeans a side of Singapore many haven’t seen before. What are some other locations that have yet to be captured on film?

Have you seen migrant workers’ dormitories or the little sliver of space people grudgingly carve out for domestic workers on film before? There’s so much our young local cinema has yet to fathom, much less explored.