“Guess where this is,” he probes.

Looking down at the postcard-sized print of lush greenery before us, we can’t—but he already knew that.

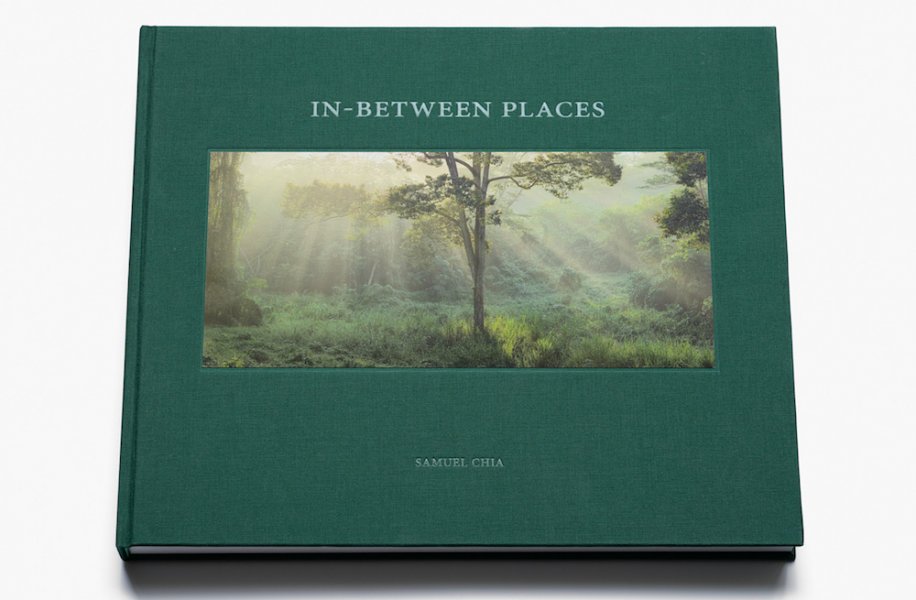

28-year-old printmaker Samuel Chia sits contentedly in his chair, gingerly caressing the pages of the massive coffee-table book he’s brought. Each one holds a delicate print of nature. “What’s really interesting is that you can take a collection of 70 photographs made of landscapes in Singapore from any photographer, show it to Singaporeans, and there should be at least one of the 70 where people can identify where it is,” he says.

“But in my book, there’s not a single photograph where you can identify the location—which should not be possible because Singapore’s way too small. There’s way too many of us, and we are quite familiar with (the island). It should not be possible to make a picture of Singapore that doesn’t look like Singapore.”

And yet he’s done it. In-between Places is less a natural documentary publication than it is a labour of love. Composed of 70 photographs of wild nature Chia created himself, it is the painstaking culmination of what he describes as a 14-year “spiritual process”. The self-taught photographer and printmaker spent 10 years journeying into untamed spaces in Singapore, photographing sights hidden to the average local’s eye—places he deemed “untouched by the hand of man”. Every photo produced was taken somewhere on the mainland island, even if their ethereal, other-worldly quality might suggest otherwise.

Sunrise and backlit grasses. Photo credit: Samuel Chia

The gem in the book lies not in its well-crafted prints, however. Instead, it’s the fact that all of the places photographed no longer exist.

“None of these photographs can ever be made again; none of them look like this anymore,” said Chia. “Some of them are still around today—they just don’t quite look like these pictures.”

For example, the magnificent tree gracing the cover—a beloved durian tree—was chopped down a year after Chia got his shot. Going down to the area more than 10 times before, he had managed to snap it in a brief window of two minutes after seven attempts; the final image was painstakingly stitched together from 20 photographs taken at five different camera positions. But the tree no longer stands.

“So in that sense, all these places have been lost,” he said.

It all began with a life-changing trip to New Zealand when he was 14 years old. Entranced by the unspoiled wilderness he saw, the self-proclaimed animal lover fell into photographing nature and wildlife—whatever he could find at the Singapore Zoo and Jurong Bird Park at the time.

“When I came back, I was struggling—I was still very young, and I was struggling with institutionalised education,” he shared. “I always wanted to escape back to that kind of world, but didn’t have the money or the means. So I decided at one point that maybe I might be able to have some of that magic in Singapore. I took out a map and looked for spots of green—the bigger the better. And I just went to these places to see what on earth there is to be found there; and slowly I found these places.”

Imminent storm at sunrise. Photo credit: Samuel Chia

Though the book was born out of personal trauma, Chia believes its greater purpose lives beyond seeing him through his hardships. He hopes it can be a conversation starter for conservation—the fact that the photos were all made in the last 10 years should be concerning enough.

“I’m not like an old man where I was photographing in the ‘60s and ‘70s, where there wasn’t much development and people could argue, ‘well duh, you’re going to find pictures like that,’” he said. “(But the future generation are) growing up in a world without these places; they can no longer find that escape.”

When asked if he considered exhibiting his elusive prints, Chia was firm in his refusal.

“A book is enduring for generations to cherish. And the idea is that this would endure for even longer than myself, and be also an ode to these places, you know, in memory of these places. To motivate, convince, inspire people that we ought to care more about these places, and if at all possible, save whatever we can,” he said.

Scorched tree and windswept grasses. Photo credit: Samuel Chia

A stickler for quality, Chia has spent the last 15 months perfecting the make of his precious book—from paper to ink, and down to the glue binding everything together. “The natural cost of each book is so high; what you see here is probably $1,000,” he estimated.

But he won’t be selling them. The personal nature of the project has made him averse to profiting from it. Hence he decided not to register his prized book for an ISBN (International Standard Book Number), completely preventing it from entering into the retail chain.

As such, the only way someone can get their hands on the book would be to make a donation to a chosen charity, after which they would be personally sent the book. Chia is currently in talks with local non-profit organisations Nature Society Singapore and ACRES.

Still, it’s a long way off; the nature landscape photographer, who runs a printing business out of his home, projects that it would take at least another year for In-between Places to be retail-ready. He is currently in the process of sourcing for funding to produce it on a full print run—in the quality he desires. If he doesn’t succeed, the book will remain in limited print funded out of his own pocket. He might cull it entirely; he’s already fulfilled his desire to send a copy to the Prime Minister for personal keeping.

“Nobody has ever looked at Singapore this way before; and nobody has celebrated our country like that,” said Chia, a hint of what looks like resignation in his eyes. “We always have people shooting the beautiful HDB flats, Marina Bay Sands; there are people that photograph the otters, the birds, things like that—nobody’s ever envisioned Singapore to be a wild landscape. Nobody even believed that was possible.”

Quite dramatically—but perhaps reasonably so—he adds, “So this will never ever be done again.”

Sacred Tree. Photo credit: Samuel Chia

Our interview with Chia continues below.

How has the process been making these prototypes of In-between Places?

It’s been 15 months just to print this book; (before that) three years to write the stories and edit the photographs. Every photograph has seen at least two 300 hours of editing—not because I photoshopped the tree into the picture, but because I’m trying to render as realistically as possible. So you’re going to see colours that are very nuanced and very realistic interpretations that are very fine. You wouldn’t see that on people’s Instagram feeds.

What prompted you to start this project?

This was never a project. It was more of a journey—where I encountered a series of traumatic experiences when I was very young, and I was looking for a path of escape, as we all do. So this was my escape at that time; and the process of going to these places, and making these photographs. I never knew that I was going to have this book, so many years later.

Did you have to recce places a few times to make sure you went at the perfect time and weather conditions to create the photos?

I don’t recce places so much as I explore them; I go into them. It’s a very spiritual process. I get to know a place better over time by making frequent visits to it. And then of course, when you’re outdoors a lot, you understand how weather works a little bit better. And then you eventually are able to make some small predictions about how things might go one way or another.

You explore and then you just immerse yourself into a place. And slowly these things reveal the relationship to you. It’s a very personal sort of thing. I’m not saying that I talked to trees; but I like to put it in a very romantic way because the whole exchange was very romantic and very spiritual.

This is like my Narnia, which is here yet not here; these are the in-between places, in the sense that they are, for one, physically in between our urban escape. But also if you went to these places, they don’t look anything like my photographs—they’re not necessarily welcoming places. There are blood-sucking insects, it’s very hot, it’s very exposed; there are no creature comforts, no flat-paved paths. So they’re not pleasant places in and of themselves. But if one is searching for serenity, in between this noise and insane, over-civilised society that we are in, there are no better places to go to than places that are very wild, where there are very, very few people.

Stay up-to-date with Samuel and In-between Places here.