After several award-winning short films and then an 11-year creative hiatus, Singaporean filmmaker K. Rajagopal will compete for the Grand Prize and the Camera d’Or at Cannes’ International Critics’ Week later this month with his debut feature film A Yellow Bird. A rare Singaporean feature with Indian protagonists, the film tells the story of a man recently released from prison as he struggles to rebuild his life and relationships.

Here, Raja talks to us about the dearth of Indian stories in Singaporean cinema, the extreme poverty he saw while making the film and the lovely meaning behind the title.

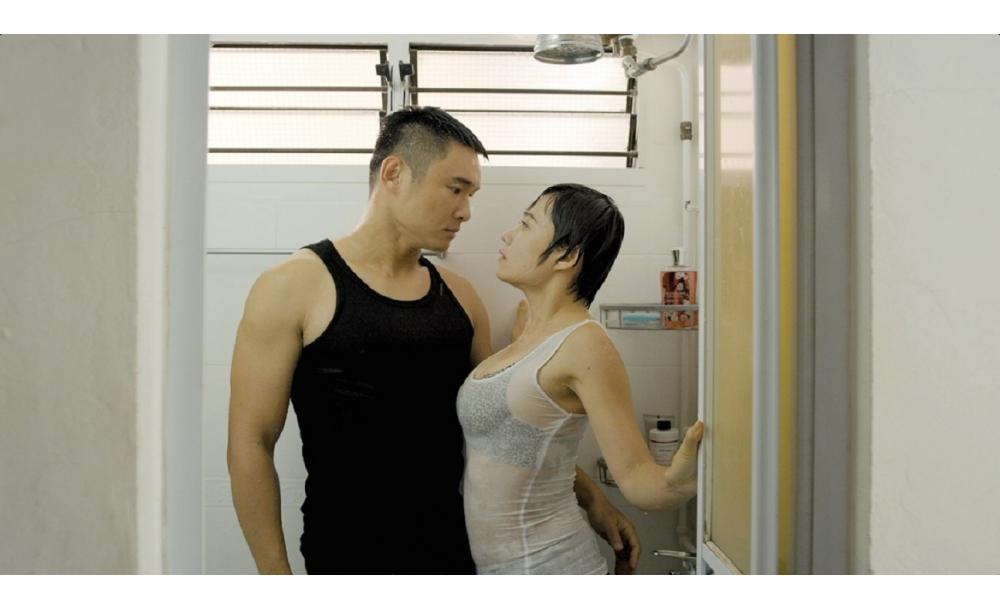

Still from A Yellow Bird

I’m third generation Singaporean. We’re Malayalees from Kerala, which was a minority group at Seletar Airbase and Jalan Kayu. My grandfather and father worked with the British Royal Air Force.

My father wanted me to learn Mandarin at school. I was in a class where it was all Chinese students.

I remember growing up not wanting to identify as Indian, because you got made fun of. My mother used to put oil on my hair and after a while I stopped because one a kid said, “Eh, so smelly.”

But when I grew up I realized it’s so cool to be Indian. I made a trip to India, and I realized there’s so much to know about the land where my ancestors came from. I started to take pride in it.

My first foray into the arts was in theater. I played the stereotypical roles—though I learned a great deal about acting and really enjoyed the ensemble work.

There was always a frustration in me because you never got the lead parts or the big roles.

I was working in Little India, moonlighting in a hotel as a night auditor. There was a new influx of Indians and Sri Lankans coming in the early 90s. There were illegal foreign workers asking me if they could sleep at the motel, and I would let them sleep on the floor because they had no place to go. They all couldn’t sleep at night, and I couldn’t sleep at night, and that’s how my first short film, I Can’t Sleep Tonight, came about.

I knew I wanted to create a voice for the Indian, and my protagonist had to be Indian.

There were Tamil movies and Hindi movies that people made fun of, but I was exposed to the parallel cinema of Kerala, the films of Adoor Gopalakrishnan, and I was really taken in.

So I went out to do I Can’t Sleep Tonight. I got a friend who was working at Mediacorp at the time and said, “Can you help me? I need a camera.”

I sent it to the only platform we had for short films, which was the Singapore International Film Festival. My film won a prize that year. And you won’t believe it—the judge was Adoor Gopalakrishnan.

I asked him, “Can I come watch you make films?” He said, “Give me five years of your life. That’s how long I take to make a film.” And of course, I didn’t go. I was young and frivolous. Well, not that young. I was 30.

I continued making shorts, and then I stopped. I got nervous because I spent so much money. In fact, I had to borrow for my last one because I made it on 16mm film. I was very insecure. Even after making three shorts, I thought I knew nothing about filmmaking.

There was an 11-year hiatus. Then Sun Koh and others were working on Lucky 7, and they wanted me to be a part of it. They were in their 20s and I was in my 40s.

I met Fran Borgia [film producer, Akanga Film Asia] doing a performance of King Lear. He said, “Why don’t you make a film? This time there’s a grant. It’s not an investment. Let’s do it.”

Still from A Yellow Bird

So I wrote A Yellow Bird in 2012—the storyline, not the full script. We presented it and we got the grant.

The title came from my childhood. My mother used to say, “If you see a yellow bird, make a wish. You’ll meet someone nice, or you’ll hear good news.” Looking out for that bird was this hope that I had in my childhood.

There have been hardly any Singaporean films that are in Tamil, with a Tamil or Indian story. That makes me think that I should do more and continue.

Our lives are not just about casinos and the financial center and a modern city-island.

You wouldn’t believe the living conditions I saw looking for a location in Little India. But every house had a TV.

The idea of the protagonist being homeless came from people living under my block, a Malay family with two kids. The woman was pregnant, and they were living on the void deck, sleeping on cardboard.

The Singapore Film Commission gave us the grant based on the script, and they made no demands. And the panel was a group of producers and festival people from around the world. They were the ones being pitched to.

I don’t self-censor, but I would to avoid hurting anybody.

I made a commissioned film, Timeless, that explored the role of the Indian man over time in Singapore. I included an Indian gay man having an abusive relationship with his partner. I was advised that I might not be able to screen it, so I removed some of the sexual scenes.

I compromised a bit because I thought, “I’ve already made the film,” and to not show the film at all didn’t make sense to me at the time. I know someone who was upset with me for allowing it to be shown cut. But I had a director’s cut shown at The Substation separately.

I don’t think there should be any restriction to filmmaking. Every film has to be taken for what it is. The rating system is fine. But even then, anyone above 18 is old and mature enough to be discerning.

Sometimes, I’m broke. I pay my bills late. Then I get reprimanded in that way that family reprimands, like “Can you please be more responsible?”

But when they came for 7 Letters at the Capitol, they didn’t expect such a hoo-ha about it. And when I told them about Cannes, they were all very happy.

My mom was very supportive. She used to cut out articles. After she passed away, I found them under the cupboard. She had religiously cut every story, even though she’d never spoken about it.

She loved films. She’s the one who told me to watch Adoor’s films. She knew my taste for films, and when she watched a good film, she would say, “You’ll like this one.”